Republished by Blog Post Promoter

CHAPTER 1: CHARLES OF CHRIST CHURCH

“When I first arrived in the great city, I had neither kith nor kin in England, and was therefore as free as air — or as free as an income of eleven shillings and sixpence a day will permit a man to be. Under such circumstances I naturally gravitated to London, that great cesspool into which all the loungers and idlers of the Empire are irresistibly drained. There I stayed for some time at a private hotel in the Strand, leading a comfortless, meaningless existence, and spending such money as I had, considerably more freely than I ought.”, I thought to myself.

It was a cold morning of the early spring. We sat after breakfast upon either side of a cheery fire in the old room at Baker Street. A thick fog rolled down between the lines of dun-colored houses, and the opposing windows loomed like dark, shapeless blurs through the heavy yellow wreaths. Our gas was lit and shone on the white cloth and glimmer of china and metal, for the table had not been cleared yet.

As neither Dr. Watson, or myself, had any other pressing matters before us, and no prospect of employment to enhance either my interest or livelihood, we spent the afternoon perusing the London Times. I read nothing except the criminal news and the agony column. The latter is always instructive, most particularly in the observation that violence does, in truth, recoil upon the violent, and the schemer falls into the pit which he digs for another.

Our original acquaintance, when I had been lodged on Montague Street, around the corner from the British Museum, was on Saturday, July 16th. I had spent the day working in the chemical laboratory at St. Bart’s Hospital. In the morning, I complained to a young medical man named Stamford about not being able to find someone to go halves on some nice rooms I had found in Baker Street.

That very afternoon Stamford brought Dr. Watson into the lab to inquire about sharing the rooms. The next day Watson and I went around together to inspect our potential domicile at 221B Baker Street. We made our arrangements then and there with Mrs. Hudson, the landlady. Watson began moving in that night, and I the next morning, Monday, July 18th.

Dr. Watson represented himself to me as having served as an Assistant Surgeon of the Army Medical Department, which was attached to the 66th Berkshire Regiment of Foot in Afghanistan. He related to me that he was discharged following an injury received in the line of duty during the infamous British defeat at the Battle of Maiwand, in July of the previous year. Watson related that he was nearly killed in the long and arduous retreat from the battle, but was saved by his orderly, Murray, who threw the doctor on a pack-horse and thus helped to ensure his escape from the field.

Watson is strongly built, of a stature either average or slightly above average, with a thick, strong neck, owing to the fact that he was once an athlete, whom, although a Scot who was educated at the University of Edinburgh, played rugby for Blackheath in south-east London.

I spent nearly half an hour lighting and relighting my pipe while Dr. Watson shuffled through the tabloid pages, grunting occasionally at one trivial report or another.

“I was never a very sociable fellow, Watson, always rather fond of moping about in my rooms”, I complained in a melancholy tone.

Watson grunted impassively from behind the unfolded sheets of the newspaper with little regard for anything other than the distraction provided by a river of typographical trivialities many men frequently employ to dull their empathy. I will admit that I have most certainly included myself amoung their number on numerous occasions.

Apparently the dampness of my environs had affected my personal blend of Latakia and Cavendish tobaccos, which I have relished as a flavor more pleasing than the finest culinary delicacies of Paris for many years. Ordinarily, the heat retained by the fine meerschaum bowl of my pipe was sufficient to dry the mixture enough to keep it well lit. In any case, matches are plentiful and cheap. Suitable pipe tobacco is not.

For some years Watson had taken it upon himself to create adventure stories based upon my criminal investigations, which, upon several occasions, he had accompanied me at my request. Most frequently, I asked for his assistance when the matter at hand presented a feature of menace which may have required fire arms. For this purpose Dr. Watson seemed inevitably prepared, bearing his service revolver in his pocket, should the occasion for the use of it present itself. Indeed, I presumed without justification, that his military service qualified him as a proven marksman, though, in point of fact, as an assistance surgeon, he had never fired a gun in defense of his country or himself.

My review of his written accounts of our adventures did not meet with my satisfaction upon any occasion. After reading a few of them I chose to ignore them more frequently than not, demurring of his insistence upon sensationalizing the science of logic and observation which were the only features of my investigations worthy of note, in my own opinion.

I had been silent all the morning, dipping continuously into the advertisement columns of a succession of papers in search of items of professional interest. Having reflected upon the subject of his scribbling as I researched the morning papers, with fruitless result, I emerged in no very sweet temper to lecture him upon his literary shortcomings.

“To the man who loves art for its own sake”, I remarked, tossing aside the advertisement sheet of the Daily Telegraph, “it is frequently in its least important and lowliest manifestations that the keenest pleasure is to be derived. It is pleasant to me to observe, Watson, that you have so far grasped this truth that in these little records of my cases which you have been good enough to draw up, and, I am bound to say, occasionally to embellish, you have given prominence not so much to the many causes celebres and sensational trials in which I have figured but rather to those incidents which may have been trivial in themselves, but which have given room for those faculties of deduction and of logical synthesis which I have made my special province.”

“And yet,” said Watson smiling, “I cannot quite hold myself absolved from the charge of sensationalism which has been urged against my records.”

I took up a glowing cinder from the fireplace with tongs and lighted with it my long cherry-wood pipe. I smoked this when I was inclined to a cooler and sweeter smoke than that provided by my briar pipes.

“You have erred in attempting to put color and life into each of your statements instead of confining yourself to the task of placing upon record that severe reasoning from cause to effect which is really the only notable feature about the thing”, I said, puffing ringlets of smoke into the air which merged and gently dissipated upon the ceiling.

“It seems to me that I have done you full justice in the matter,” Watson remarked with some coldness.

“It is not a matter of selfishness or conceit” said I, answering, as was my wont, to his thoughts rather than his words. “If I claim full justice for my art, it is because it is an impersonal thing — a thing beyond myself. Crime is common. Logic is rare. Therefore it is upon the logic rather than upon the crime that you should dwell. You have degraded what should have been a course of lectures into a series of adventure tales.”

“At the same time,” I remarked after a pause, during which I had sat puffing at my pipe and gazing down into the fire, “you can hardly be open to a charge of sensationalism, for out of these cases which you have been so kind as to interest yourself in, a fair proportion do not treat of crime, in its legal sense, at all. The small matter in which I endeavored to help the King of Bohemia, the singular experience of Miss Mary Sutherland, the problem connected with the man with the twisted lip, and the incident of the noble bachelor, were all matters which are outside the pale of the law. But in avoiding the sensational, I fear that you may have bordered on the trivial.”

“The end may have been so,” he answered, “but the methods I hold to have been novel and of interest.”

“Pshaw. My dear fellow, what do the public, the great unobservant public, who could hardly tell a weaver by his tooth or a compositor by his left thumb, care about the finer shades of analysis and deduction?! But, indeed, if you are trivial I cannot blame you, for the days of the great cases are past”, I said with an earnestly disheartened conviction.

“Man, or at least criminal man, has lost all enterprise and originality. As to my own little practice, it seems to be degenerating into an agency for recovering lost lead pencils and giving advice to young ladies from boarding-schools. I think that I have touched bottom at last.”, I said in a black, disgruntled mood.

For some considerable time we sat wrapped in silence. I contemplated the flickering embers of the fire, intrigued by the inexplicable, spontaneous conversion of matter into energy for which no reasonable explanation had ever been offered by any of the great minds of science or philosophy.

Watson continued rattling and shuffling through a pile of papers which I had already discarded with overwhelming disinterest. There was seldom much of any interest to me in the press, unless it reported upon some incident or situation which offered a game of investigation to me.

After some little while, Watson reported to me that he had chanced upon a curious article concerning the mysterious disappearance of a young girl.

“Have you already read it?”, he inquired.

“No, I cannot say that I recall it. If there is a feature about it that strikes you as being of singular interest, perhaps you will be kind enough to share it with me”, I said.

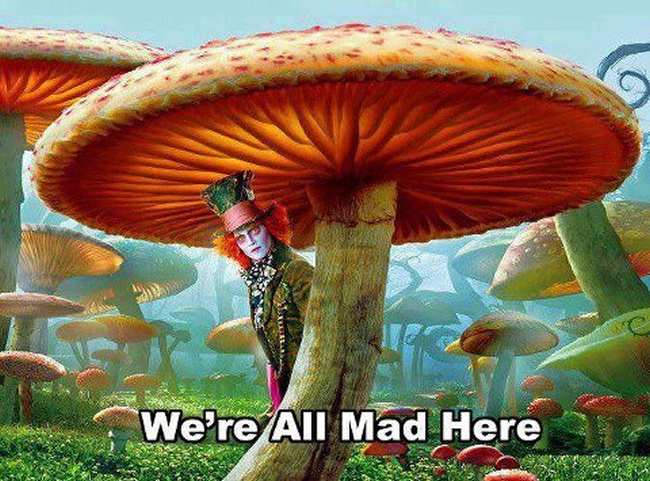

According to the report, he summarized, a female child of about ten years was reported missing for several hours by her two siblings and a professor of mathematics, currently at Oxford, while enjoying a Sunday outing along the river Thames. The girls, when interviewed, stated that their sister, Alice Liddell, had been chasing a white rabbit, and had apparently followed it down a rabbit hole and disappeared beneath an enormous elm tree! The child remained missing for several hours.

Watson read the section of the report which specified certain details of the case he thought I might find relevant, as follows:

“April 19th. The Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson and the Reverend Robinson Duckworth rowed in a boat up the River Thames with three young girls: Lorina Charlotte Liddell (aged 13), Alice Pleasance Liddell (aged 10)and Edith Mary Liddell (aged 8). The three girls are the daughters of Henry George Liddell, the Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University and Dean of Christ Church as well as headmaster of Westminster School. The journey had started at Godstow, a hamlet on the River Thames northwest of the centre of Oxford.”

“Naturally”, Watson said, paraphrasing the report, “the family of the child, upon news of the incident, were highly distressed. The professor in question, a Mr. Dodgson, has not been detained by authorities, but several unnamed persons have asserted suspicion of pedophilia against this man!” Watson paused as he completed reading the remaining portion of the article.

“How very curious”, he remarked, placing the paper next to his chair, and pulling out his own smoking pipe, tobacco and tools. “The siblings of the child insist that all parties involved are entirely innocent. They assert that their sister is at fault for chasing a strange rabbit. Indeed, they claimed that the rabbit was wearing a waistcoat, and examining a pocket watch when they last saw it!

Furthermore, the child in question, Alice, when questioned by the press, stated emphatically that much ado was being made of nothing, and that the entire incident was merely a story conjured by Mr. Dodgson as an innocent amusement! Certainly, the entire matter is nothing more than a sensational hoax, perpetrated by the Times editor as an attraction to gullible persons to read the paper. Typical behavior of the press! Reprehensible, I should say” , he concluded.

I pondered and smoked over the matter for several moments, mesmerized by droplets of rain streaming down the panes of glass which faced westward from my upstairs rooms at 221 B Baker Street.

“Certainly”, I observed to Watson, “this report demonstrates that the magistrates investigating the case are mentally incompetent. The family, powerless to press charges in the matter, as there is no evidence of foul play, and no harm having been done, are powerless to prosecute.”

Nevertheless, I seized upon this peculiar report as an opportunity to busy myself with a new investigation. My curiosity pressed me to make an inquiry with the constabulary under whose jurisdiction the matter had been attended.

However, before turning to those moral and mental aspects of the matter which present the greatest difficulties, I reminded myself, the inquirer must begin by mastering more elementary problems. After all, it is a capital mistake to theorize before you have all the evidence. It biases the judgment. To that end I posted a telegram that very afternoon to the constabulary at Oxford to whom I was known personally through our cooperation upon several cases in that area.

The following morning I received a reply from which I discovered that Mr. Dodgson was a bachelor Anglican clergyman. Moreover, and most importantly, a comfortable livelihood was provided him through his talent as a mathematician, which had won him the Christ Church Mathematical Lectureship.

No formal charges had been filed against Mr. Dodgson or Reverend Robinson Duckworth by the girl’s father, the Vice-Chancellor. However, the telegram implied that the inferred scandal of sexual indiscretion fomented by the newspaper report remained a topic of discussion upon the campuses of the university as well as in the community at large, and had alerted the constabulary to maintain an informal interest in the matter.

Contrasted with this supplemental information, the scandalous implications regarding his behavior, as described in the Times report, were becoming more intriguing to me by the moment! The most singular feature of the case, for me, was not the possibility of indiscretion but rather that no further mention whatever had been made of the rabbit!

Having no further information available to me, and disdaining contact with the press, as was my usual practice, I determined that my most effective method of investigation was to go around to visit professor Dodgson at his offices at Christ Church.

As for the matter of Mr. Dodgson’s integrity, rather than assuming that an impropriety might have occurred, it seemed more likely to me that his ignorance was as remarkable as his knowledge. As a mathematician he is undoubtedly astute, given his position as a professor. However, an unmarried man of his position should most certainly understand that his culpability for the temporary disappearance of this child placed him at the greatest risk socially! The penchant for society to persecute such a person, even a clergyman, in the absence of evidence of his innocence, is certainly a matter of gravity, if not sensibility.

I might easily have dismissed the matter entirely if it were not for an abiding curiosity on my part to reconcile the singular incongruities in the report. How could a young girl, and not her siblings, disappear down a rabbit hole for several hours, having been observed, reportedly, in pursuit of a rabbit wearing a waistcoat and possessing a pocket watch? Further, why would the children assert that the incident was merely a story conjured by Mr. Dodgson for their amusement, when the adults in attendance at the scene treated the matter with so much earnestness that the police and press were summoned?

— END OF CHAPTER ONE —

—

Read Chapter Two here: https://lawrencerspencer.com/2011/01/22/sherlock-holmes-my-life-chapter-two/